An informal review of anthropic qualia states

Posted on 18 June 2024 by

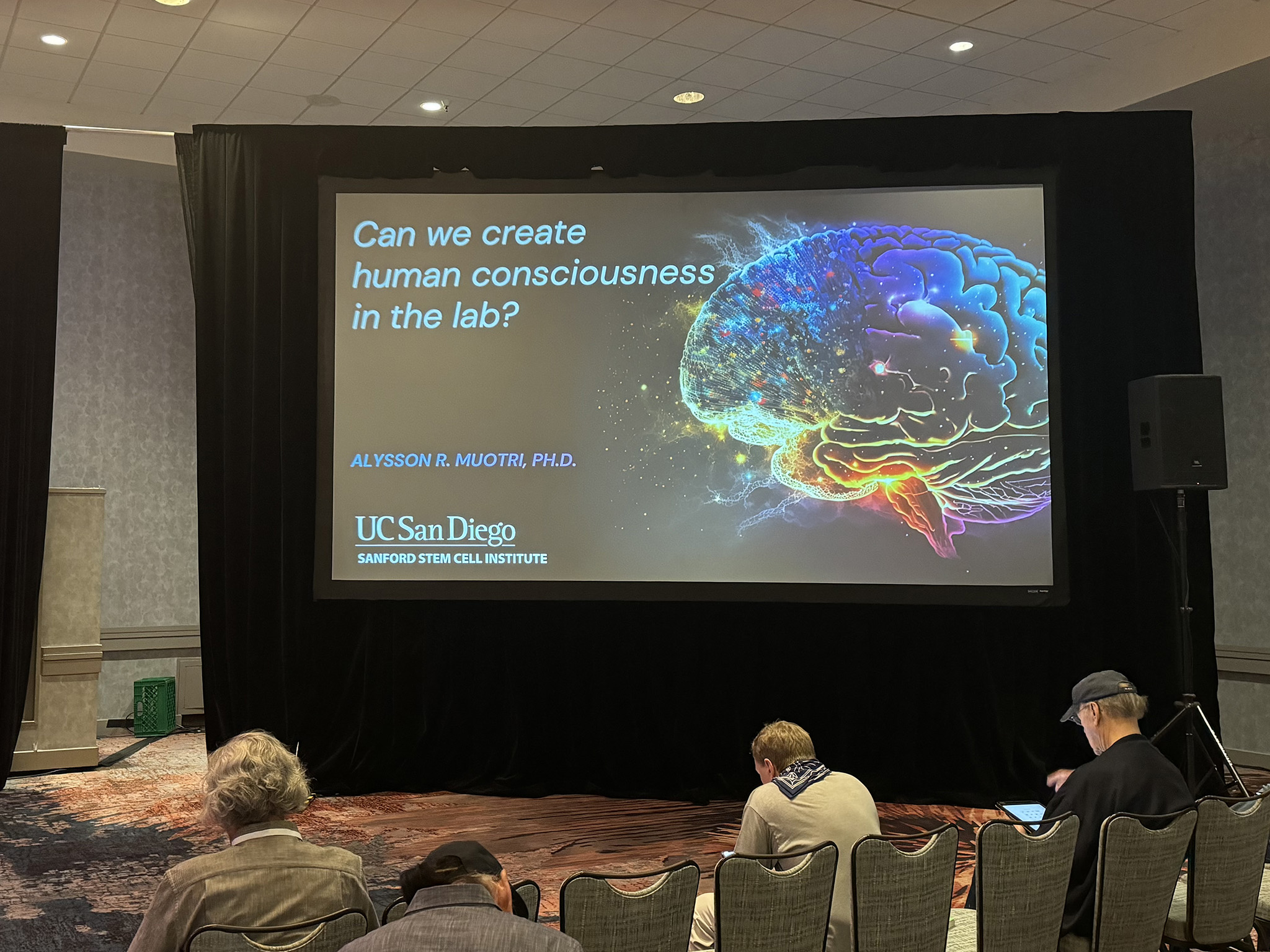

A couple of months ago I visited Tucson, Arizona, where I attended The Science of Consciousness Conference – a biannual gathering of an eclectic mixture of scientists and philosophers who descend upon the Sonoran desert to discuss the nature of consciousness in an open-minded environment.

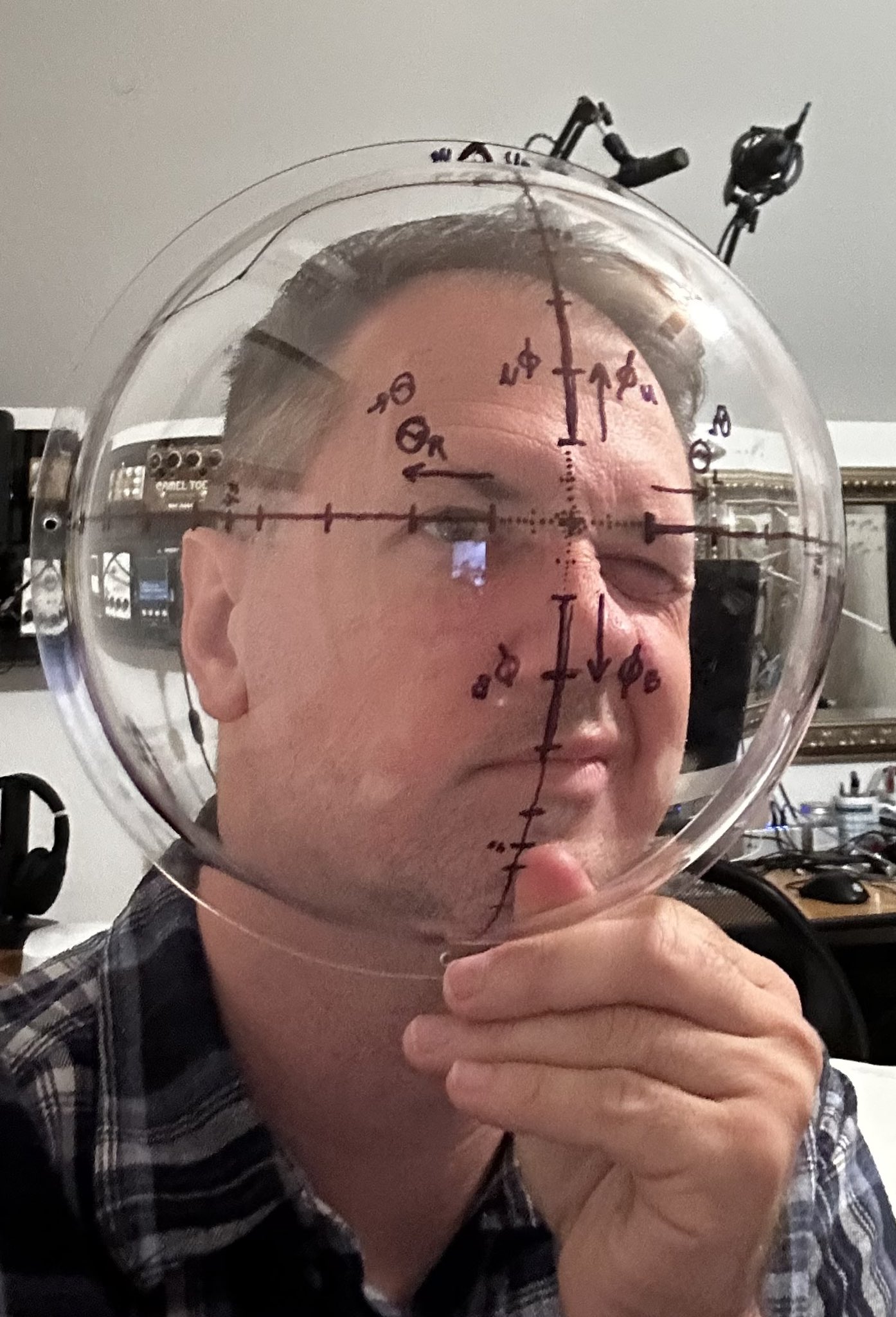

Some highlights included catching presentations by Shamil Chandaria on Bayesian brain theory, Brian Lord on transcranial focused ultrasound, and Alysson Muotri on whether or not cerebral organoids possess consciousness – but I was most overjoyed to finally sit down and compare notes with my fellow phenomenologist, Brad Caldwell, who had decided at the last minute to come all the way from Alabama.

Brad is the author of Rings of Fire, a 160-page magazine-style book which details an original phenomenological framework for describing human qualia, while also speculating as to what their neural correlates might be. I was eager to sit down with him to establish the overlap between his framework and those used by other researchers like Steven Lehar and Andrés Gómez Emilsson. The conversations we had made my brain start to whir.

What is qualia structuralism?

Mike Johnson first defined the terms qualia formalism and qualia structuralism in his treatise on consciousness, Principia Qualia:

Qualia Formalism: for any given conscious experience, there exists – in principle – a mathematical object isomorphic to its phenomenology.

Qualia Structuralism: the mathematical object isomorphic to a conscious experience has a rich set of mathematical structures.

I think Brad’s project is a qualia structuralist project – as is my own. At my end, I have previously attempted to define a prototype working model for a momentary qualia state – noting that at the time of writing I expected any actual mathematical object isomorphic to phenomenology to be far more general than this:

From the top down, we have:

- The worldsim, which contains:

- the worldsheet, a two-dimensional surface where each point has both:

- depth, a scalar value, and:

- colour, a three-vector value; and:

- the worldfield, a three-dimensional vector field.

I should also note that I have since stopped using the terms worldsheet and worldfield in favour of visual field and somatic field, respectively – and collectively, I shall refer to these as the phenomenal fields.

Much of what I do is simply gathering phenomenological reports from a wide variety of sources while attempting to synthesise them into a patchwork headcanon. I’ve now gathered enough research and personal experiences that I feel comfortable making further speculation as to the true structure of the phenomenal fields, but mostly I just wish to spread what I have out on the table so that others can take a look. Epistemic status: work in progress.

Why would anyone want to do this?

I regard the construction of a model of anthropic qualia states as a step towards solving what Mike calls the reality mapping problem – how do physical states map onto qualia states, and vice versa?

I like to think that such a model will have applications in a number of areas:

- In the immediate term, I hope that this will help improve the way we communicate about qualia states.

- In the short term, I hope that this will help inform how we might construct experiences or even neuromodulation protocols that manipulate physical states in order to generate desirable qualia states.

- And in the long term, I hope that this will help inform how we might construct experiments to test the viability of a given theory of consciousness, be it physical or computational, classical or quantum.

Because if there’s one thing that the conference convinced me of, it’s that coherent theories of consciousness may soon be more urgently needed than ever.

Qualia space

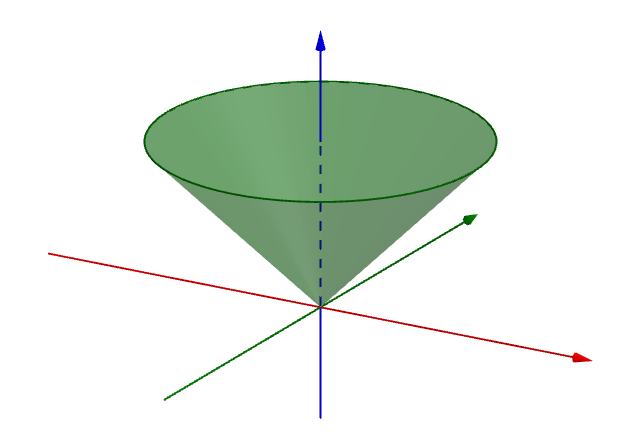

The mathematician Richard P. Stanley proposed that qualia space is a closed pointed cone in an infinite-dimensional separable real topological vector space:

Maybe something like this would capture everything – but at the same time, this is far too wide a state space for us to draw useful conclusions from.

The only qualia states we currently have access to are human ones, so starting with baseline human phenomenology – and incorporating edge cases from altered states, such as those facilitated by meditation or psychedelics – I’m going to explore the human sensory modalities and see what commonalities we can find between them. Perhaps we shall find that their state spaces are less disjoint than we might naïvely assume.

Before we start, I’d like to call upon Daniel Ingram’s advice on insight practice, in order to set the tone for this exercise in introspection:

Insight practice can seem more daunting, complex, or bizarre than other forms of practice. However, it is oddly simple. There are six sense doors. Sensations arise and vanish. Notice this for every sensation. These are cave-man simple instructions, yet somehow people make them much more complex than they need to be.

Phenomenal field unification

I often find myself returning to the question of whether or not the various sensory modalities – touch, sound, taste, smell, vision, and so on – coexist within the same space. As I have written previously:

One thing that touch, sound, taste, and smell share in common is that they are all localised phenomena – they happen at a particular location in space. We don’t hear a sound in our ears; our brains perform some incredibly impressive calculations to estimate its location before injecting it into our worldsim as localised worldfield pertubations.

So what gives these pertubations their distinctive phenomenal character? Without getting into too much depth, I’d say it’s the dynamics of the oscillatory processes that reify them. Sound has high bandwidth and low spatial precision; touch has low bandwidth but high spatial precision – and their afterimages work in different ways, too. When music stops playing, you might continue to hear a short loop in your head; but touch afterimages tend to manifest as a persistent model of your immediate surroundings.

Firstly, I’ll explore why I believe that these four modalities, amongst other phenomena, coexist within a unified somatic field. Then secondly, I’ll explore how this might be reconciled with a visual field which contains a radically different sense modality.

The somatic field

During my conversations with Brad, we discussed the state space of somatic sensations. In his phrasing: an invisible three-dimensional canvas which can morph in non-Euclidean ways. Debatably, I suspect that this state space may also support higher-dimensional phenomena.

So what about the sensations which inhabit this space? What structure do they have? As I wrote in my previous post, What is a bodymind knot?:

A body map can be a highly ephemeral thing. I can recall being quite young when I noticed how my sense of having a body would come and go as I ran my hands over my skin – just a hollow shell of sorts, its gossamer texture sporadically illuminated by the spotlight of attention.

Proprioception, interoception, equilibrioception. Mechanoreceptors, thermoreceptors, chemoreceptors. A gentle breeze over open skin. The warmth of the sun.

Touch sensations exhibit a tremendous amount of variety, but their commonality is that they all contribute to a unified body map, and can therefore be said to occupy a location in subjective space relative to one another. Many of these sensations develop semantic attachments over time which obscure their true nature, but by cultivating sufficient sensory clarity I believe the careful observer will find that these are all ultimately reducible to pertubations in the somatic field, which in some cases could be said to have a spatiotemporal texture in the region of interest – sometimes harmonious, sometimes noisy like television static.

By way of rudimentary examples, perhaps the sensation of a pinprick would correspond to a small, sharp deformation in the field; while something like heat might correspond to a drifting effect with a particular noise profile – though I lack the clarity to tell.

I think we can also work taste into this ontology. It’s clearly spatially located, co-occurring with touch sensations on the tongue, of course – but they have a more striking phenomenal character. Perhaps taste could be built out of something like dyadic vibrations, tuned by evolution towards consonance or dissonance in order to generate an attractive or aversive response in the organism?

I feel hesitant to comment on smell, as I fear I’d be treading on the toes of our resident perfume expert, who has much to say on this matter. Andrés would split the state space of scent qualia into two components:

- Aromachemicals that are “character impact”

- Flavor-like vibes

I think there’s something to the idea of these things being vibrations, as subjects will reliably sort different odours by pitch. I have watched as Andrés ran a scent workshop at a Twitter meetup in Dolores Park, passing around bottles of essential oils as people discussed whether they thought the may chang or the ylang-ylang had a higher frequency.

This aspect of smell is clearly also spatially located, but if I am sufficiently attuned I also find this additional component, which subtly permeates my sensorium and filters its global character. I believe that emotions work in a similar manner. For instance, I notice that my sensitivity to touch sensations varies tremendously from mood to mood – as if everything is run through a filter that might amplify or attenuate harsh frequencies, adjusting the global timbre or texture of my experience.

I also find that stronger emotions can manifest as concrete larger scale phenomena in specific locations; once I figured out how to feel emotions in my body – as they say – when I place my attention upon my feelings of anxiety I notice grungling patterns down in my gut; and if something startles me while driving then fear is felt as an attention-grabbing knock upon my heart.

I’d also classify meditation-induced energetic phenomena and psychedelic-induced body load as instances of the same – and will note that some of these can generate sensations outside the body map, or even dissolve it entirely.

Finally, the phenomenon of sound presents interesting challenges. Do we perceive sound out in space or on the body? In Brad’s words, perhaps sound is revealed by its pertubation effect on the frames – precise acoustic vibrations, mapped on to the somatic field in such a way as to orient the listener’s attention to the location where the sound may have originated. Confusing maybe? I’ll return to this idea when we discuss how the visual and somatic fields map onto one another, because I think it operates on similar principles. In the meantime, I’d like to think that the observant ketamine user may have noticed sound and touch melting into one another while listening to the right kind of music.

I could easily devote a few thousand more words to the labourious task of exploring how many seemingly unrelated phenomena could be cut from the same cloth – but we need to move on, there are some points I would like to make. So, here’s our invisible canvas: can we add some paint?

The visual field

While I was at the conference, the meditation teacher Roger Thisdell published a video. My flight out of Tucson was delayed, so I put it on while waiting around in the terminal. I was delighted to find that this video was all about collapsing the distance between the visual and the somatic:

Most people start off with their experience constructed such that feeling is associated with the body – obviously – and I feel here, and I don’t feel out there. But I can see the broader horizon around me and this seeing is happening kind of over there, so there’s a distancing effect like that.

Now, if you get sensitive enough, you actually come to realise that everything you see you also feel. So everything you see does trigger somatic sensations.

Roger goes on to describe the kind of practice by which one can learn how to observe these sensations:

One way to increase your sensitivity to somatic sensations is a lot of body scanning meditation, really going into detail, becoming more attuned to finer-grained sensations. And then consequently after having done a lot of body scanning meditation – typically we do this eyes closed – then graduating to another type of scanning – eyes open, and scanning the whole experience space. Eyes open, not moving your eyes, and just feeling through the whole space.

And even though you’re not moving the center of your eyesight – the fovea – you can scan through your awareness what is in all of vision, and notice that it does correspond to somatic sensations. For seeing – predominantly, particularly in the head. There’s a sense that we see from our head. Or from our face. So what you feel will create subtle sensations.

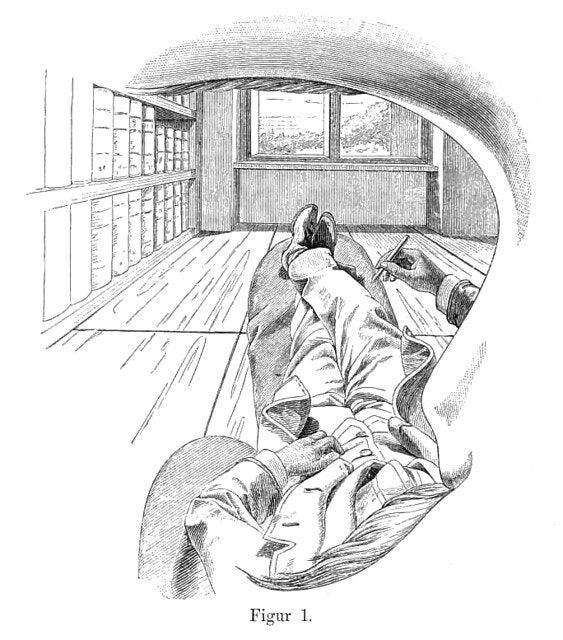

But he also has a simple demonstration using a pen:

Can you take something like this – and move in relationship to it, and notice that you can track sensations here? There’s a prediction of, like, where it would stab you – particularly in the eye.

The cool thing about recognising this connection is this is how we can begin to blend that sense of inside and outside, to recognise that it’s not me feeling over here, and then the outside world being seen over there. It’s this whole thing – it’s being felt – this whole thing is my body, like an extension of my body.

You’ll start to get this connection, and then you’ll can get into a lens of it’s still like, well – there’s seeing over there which then triggers feeling over here – and then we can kind of play with that, is the seeing there and the feeling here? And then maybe we can begin to bring the seeing here or bring the feeling out there – but eventually then we can see the emptiness of all that, collapse all that. And then there’s an intimacy of feeling and seeing.

So this is just a cool phenomenological hack, and when you really get this – this is how you begin to have the experience of feeling the world.

Talk about a pointing-out instruction. I recommend watching the full video, as well as finding a pointy object to play around with.

I recalled a conversation I’d had with Roger some time ago, in which he’d gently tried to steer me away from the bubble world model of perception from Steven Lehar’s school of thought, resembling a homunculus in a fishbowl. It joins up at the ears, he’d said.

I spent a few months mulling that one over. I think my body map has always been a bit flaky, and find I possess a fair amount of agency over “where” I might experience somatic sensations. I described one way of accessing this in my post on bodymind knots:

The somatic field does not always seem to relate to the visual field in a consistent way. There’s a somatic puzzle of sorts which I like to prompt people with: Blink your eyes, while maintaining awareness of sensations on your eyelids. Where are those located in space relative to your visual field?

When I do this, I find myself able to flip my body map between two interpretations:

- The somatic sensations form two small eyelids, suspended in front of the visual field

- The somatic sensations form one giant eyelid, enclosing the visual field

If I continue to play with this I find I can eventually collapse the distance between the two. I open my eyes and I place my attention on the sides of my head, and I find that the somatic field and the visual field do kind of join up at the ears, in a messy, fuzzy way. If I observe carefully, although some of the somatic field spills off the sides, generally I do find there is a continuous, bidirectional mapping – a diffeomorphism – from somatic field locations to visual field locations. If I hold the whole structure gently in awareness, the illusion of distance between the two seems to collapse just as Roger describes.

I will confess I found this kind of alienating. I was a bit attached to being a homunculus in a fishbowl. I didn’t want to be this weird distorted flat thing – I felt like I’d been hit with a dimensionality-reduction weapon.

This way of seeing warranted further interrogation. I constructed another experiment:

Hold your hand in your field of view, and use your other hand to simultaneously touch the near and far sides. Ask yourself the following questions:

- Are the sensations on the near side of your hand in front of the visual field?

- Are the sensations on the far side of your hand behind the visual field?

- Are the sensations on the near and far sides of your hand meaningfully separate from one another?

When I do this I find the illusion of distance breaks down in a similar way. And, as Roger tells me, if I was to get fast enough at noting I would notice that it’s impossible to put attention on both the near and the far side sensations at the same time – attention flickers between the two from frame to frame.

Phenomenal field interference

Throughout the conference, myself and Brad had already been toying with the idea that the visual field could be embedded within the somatic field, and now Roger’s video had shown how to feel into this idea.

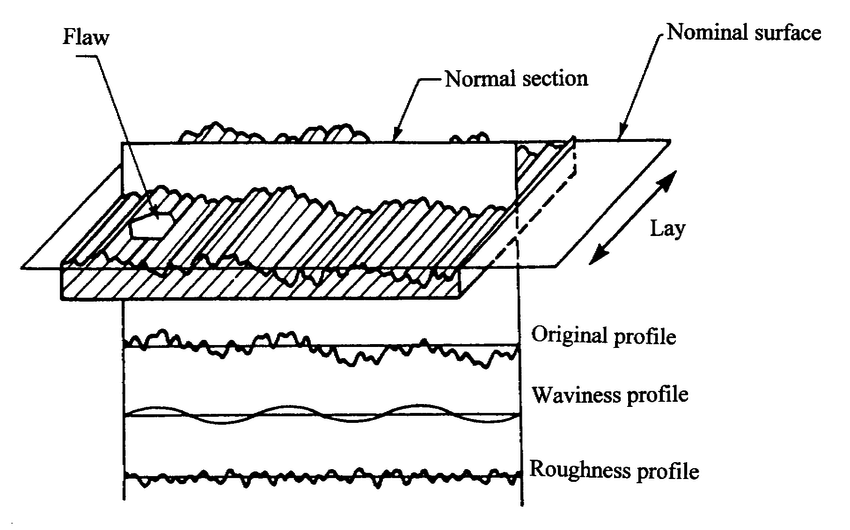

Steven Lehar proposed that if the visual field is constructed from non-linear waves, and if the substrate underlying these could adjust its refractive index on the fly – increasing or decreasing the wave propagation rate – then this could be used to compensate for depth in a way that ensures that the frequency spectrum of the waves reifying similar percepts remains invariant across a range of scales.

This is how a sense of visual field depth could be created, while ensuring that vibe-based object recognition still works. It would make sense that somatic field geometry could be constructed in a similar way.

Now, if the visual field operated on a different frequency band to the somatic, perhaps a much higher one – and if the substrate underlying them could adjust the wave propagation rate at these different frequency bands independently, then if waves in these different frequency bands were mostly non-interacting then the spaces created at these frequency bands could exhibit different geometries while remaining co-located.

I said mostly non-interacting. If you understand Lehar’s model, you’ll also understand that as depth decreases, then propagation rate increases. Then perhaps as an object comes closer to you, its waves in the visual field would interfere with the waves in the somatic field in a way that generates a low-valence, attention-grabbing aversive sensation on the corresponding part of the body? This could be an efficient way of orienting attention or even implementing obstacle avoidance.

An informal model

Once I’d returned from Tucson, I went out for lunch with a friend and we split a pair of chopsticks and spent some time pointing them at one another. We found that the effect is stronger when someone else is holding the pointy object – this might be a factor of uncertainty as well as something to do with the self-other distinction – maybe the waves are going in opposite directions.

There’s so much more to explore. I hope the reader can see that this way of thinking is fruitful and can be used to propose novel hypotheses about subjective experiences – some of which might even be testable in the long run, with the right psychophysics experiments.

I said I would try to update on my previous model. I will reiterate that I don’t expect this to be remotely close to a complete model – though in that regard I suspect that Andrés may be making some progress at his end. In any case, here is my current working model of typical human qualia states:

- There is a single phenomenal field.

- All sensations are waves within this field.

- Different sensory modalities are distinguishable by the characteristics of these waves, of which the primary distinguishing characteristic is frequency, but there are also others such as texture.

- In some cases, the distinction is so unambiguous that it is meaningful to speak of separate fields for different sensory modalities, such as the somatic field and visual field.

- Within these separate fields, variable wave propagation rate is used to implement a variable metric. This permits the separate fields to have separate yet diffeomorphic geometric structure.

Now that we have established our model, we can celebrate by trying to break it. For instance, I am still perplexed as to how colour might fit into this model. It remains a special case, and I am no closer to figuring out what it might be – though perhaps the visual field’s elastic nature will provide some hints. And did I also just implicitly claim that the unified phenomenal field is two-dimensional? That sounds like it needs fact-checking – but if that is the case, that seems like the kind of thing that could have implications for the reality mapping problem. And finally, how might all these things interplay with phenomenal time?

These seem like great topics for future posts, but in the meantime, I welcome anybody who wishes to poke holes in this particular smooth manifold. I’d love to hear from you via email or Twitter – I welcome exasperated messages from meditators and mathematicians alike.

What is valence structuralism?

Before we end, I’d like to return to the issue of valence. In Principia Qualia, Mike Johnson also defined the terms valence realism and valence structuralism:

Valence Realism: valence (subjective pleasantness) is a well-defined and ordered property of conscious systems.

Valence Structuralism: valence has a simple encoding in the mathematical representation of a system’s qualia.

Presenting a compelling case for valence realism is beyond the scope of this document, but I should be clear that I consider this project to be both a qualia structuralist and a valence structuralist one. This means that I am also on the look out for phenomena which might constrain the possibility space of candidate theories of valence.

I want to ask: where do we feel valence? Do we feel valence in the visual field? I asked around; it seems that the straight answer is not really. This might seem like an obvious statement, but now we get to ask another question: why don’t we feel valence in the visual field?

Is it due to a particular geometry or dimensionality? Its frequency? The colour? Is it because the waves of attention flow in a particular way? What makes it so special? Lack of valence in the visual field has some interesting implications – namely, that there may be sensoriums without suffering, in Nick Cammarata’s words.

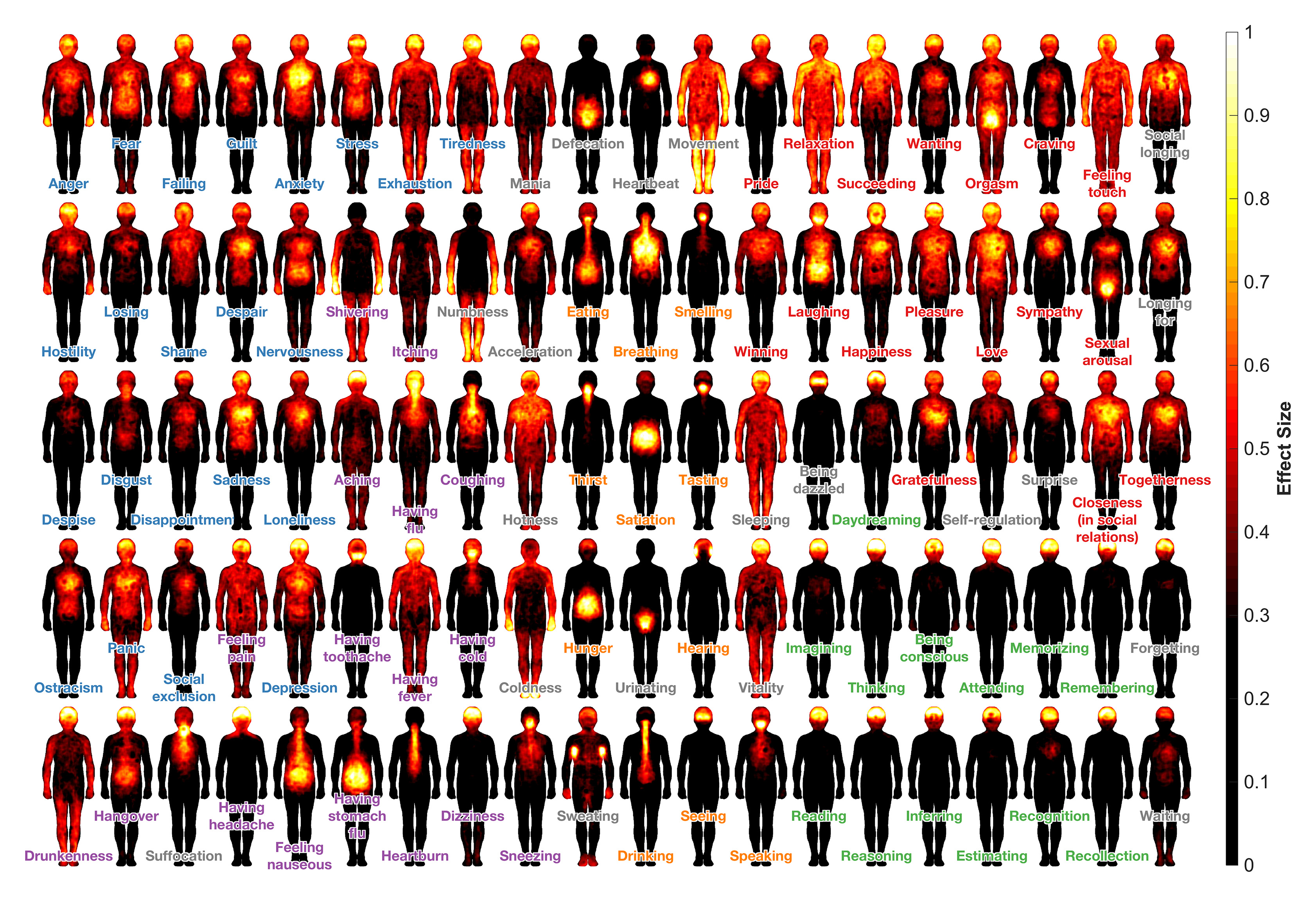

What this tells me is that any theories of valence we come up with will need to take this into account – and that any psychophysics experiments we might craft to study them may need to focus on sensations in the body.